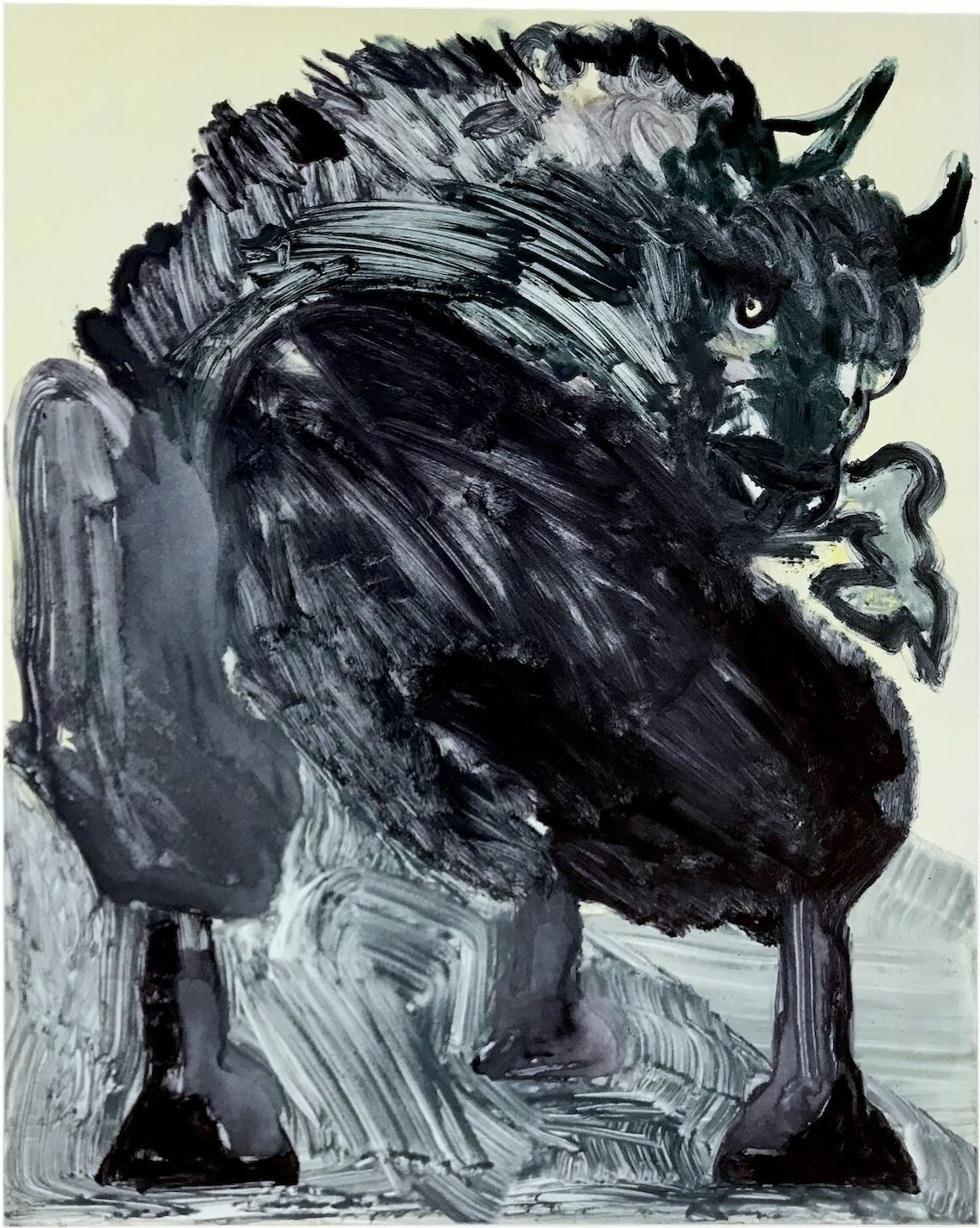

Our cover image for this issue is Hannah Wilson’s The Folder (2022). The work depicts a man, shoulders hunched and bent forward, his balding crown exposed and his gaze directed downwards. His head casts a long shadow over his left shoulder as it bows over his chest. The paint here is particularly dense, the contrast is dramatic, the darkness flat. The man’s shoulders become a kind of horizon, improbably high, broken only by a few lines of fine hair. The background, a pale grey-blue, evokes the sterile walls of a warehouse or an office, some unforgiving workplace rendered the shade of a cartoon sky – giving a half-hearted impression of escape.

Wilson works primarily from film stills, carefully selecting, cropping, and redrawing until they have found a composition. Face obscured, setting unclear, The Folder draws attention to the details it excludes as much as those it contains. The subject wears a cobalt, crumpled worker’s jacket, once a uniform of manual labour, now more familiar as the affectation of a middle-class creative. There is a sense of resignation, but from what it’s not clear.

A similar feeling threads its way through several of the essays in this issue. In Top Floor Tales, Hayley Jane Dawson recounts a journey home from an exhibition opening in Glasgow, unearthing the layers of personal history woven into a well-trodden route through the Southside. It outlines two worlds: the working-class city on one hand, and the middle-class art scene on the other, drawing out some of the tensions and pressures around keeping a foot in the door of each. That movement continues with a piece in our Metacritical series by Lisette May Monroe, about the long drives she sometimes goes on with a friend. Recounting one particular detour to a museum of chewing gum in Arizona, Monroe speculates on the function or lack thereof these journeys perform, about the idle car-games and conversations that contain real issues at heart, about the universal need to ‘divert’ one’s time and the privilege of having that recognised as art. Framed by a looping image of an artist donning and discarding his Deliveroo uniform, knotty relationships between class, time and creativity also run through Kate Morgan’s review of Teddy Coste’s The Junction at Lunchtime and Gregor Horne’s New Work Scotland at Celine.

Ruby Kuye-Kline, RED HOLE, 2022, painting previous to being blacked out in ink, oil paint on canvas, 180 x 120 cm.

Elsewhere, Kiah Endelman Music speaks to artist and filmmaker Michelle Williams Gamaker. Touching on projects including the Women of Colour Index, her Dissolution film trilogy, and the institutional collective A Particular Reality, Gamaker discusses the role language has played in her work: drawing together real and fictional activism, creating the possibility of critical affection and enacting an interrogation, immersion or escape.

In The Sharp Wheel That Loves You, Georgia Horgan dissects the appearance of Japanese anime in Mexican culture since a series of international trade agreements beginning in the 1980s. She registers anime’s contemporary influence in the work of millennial artists Mauricio Orozco and Luis Campos as an emotional symptom of a distinctly neoliberal condition. For The Limits Of … column, Rachel Grant unpicks the links between the oil industry and culture in Aberdeen, outlining the insidious effects it has had on the city’s art scene and asking where and how forms of fossil fuel divestment might take place.

Aya Bseiso’s Impossible Terrains meditates on the intimacy held in contested landscapes, the memories that course through the watery border between Palestine and Jordan, and asks ‘How to Return?’ Kandace Siobhan Walker’s SEINE was first presented at Chapter Gallery in Cardiff, alongside a film, photographs and a delicate net suspended from the ceiling and made by the artist herself. In the poems, the net ‘WEARS THE DEAD LIKE JEWELLERY’, and pulls in the stories of her childhood.

In our reviews section, Maria Sledmere responds to Elvia Wilk’s recent book of essays, Death by Landscape, plotting the points where a first person ‘I’ transforms from a glyph to a stalk that wraps itself around essays on the climate, fandom and the weird. Rodrigo Vaiapraia reviews Holy Bodies by Clay AD in light of Raphael’s painting The Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia, considering the book’s queer interweaving of the spiritual and bodily. In their review of Suds McKenna’s exhibition, A familiar plough into the knot of a tie, Romy Danielewicz describes the queer communality the works depict, a hedonistic imaginary of lives lived in a ‘mutability of presentation’. Andy Grace Hayes reviews Scott Caruth and Alex Hetherington’s exhibition Seen and Not Seen at CCA, Glasgow, disentangling the ‘migrating sounds’ of the two artists’ work and asking if they are in conversation or competition. In A Letter from Newcastle and Gateshead, Caitlin Merrett King recounts a weekend of openings and music in New Narrative style.

In her review of Agitated Air: Poems After Ibn Arabi, Nasim Luczaj notes how the movements of Yasmine Seale and Robin Moger’s retranslation perform love as a site of renegotiation and recapture. Reviewing Camara Taylor’s show at Collective, Maria Howard draws links between memory and water in the context of the artist’s research on Scotland’s links to the slave trade. Finally, Hussein Mitha reviews Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s installation at The Common Guild ‘May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’ reflecting on the show’s treatment of the 2011 Arab Revolutions in ‘strangely melancholic images, charged with unfulfilled potential and lost hopes’. A negative image is not necessarily a symbol of defeat, they argue: rather a way of rendering their subject with vividness.