Hayley Jane Dawson

I’ve spent the evening at an opening and there I tell someone I often contemplate giving all this art shite up. How sometimes I wish I was just a wee Glesga wummin, cleaning my close with a brush and soapy water, knowing all my neighbours’ business and keeping my house clean so folk can’t say it’s a cowp.1 I’m walking back through the Friday night rush to catch the train home, and as I pass into the belly of the Central Station bridge, there is a big crowd. It turns out it’s a queue for free food and toiletries, a street ambulance providing for those in need. People wait for potatoes and rolls in the middle of the city, whilst other folk pass by on the way to dinner or the pub with pals.

I’m feeling guilty tonight, as I stroll home from the exhibition of a friend, a fellow working-class person trying to navigate the (mostly) upper-class art scene. The shame of class hangs over me, ever present. Who do I think I am, complaining about my part-time job and lamenting about representation within the arts, when my parents and grandparents never got to choose what they wanted to do with their life. They had children to support and did whatever was necessary to make ends meet. I so desperately want to be an artist; always have done, since my granda taught me to stay within the lines of my colouring in books. But now I struggle with reconciling my roots with the pan loafie2 art world I also have one foot in. I wince when I think about how earlier in the evening someone had turned their back on me as I was mid-sentence, finding someone more important to talk to in the toilet queue at the gallery. I waited my turn in line then left immediately afterwards, rejecting the players of the Glasgow art scene right back for not deeming me worthy enough of a conversation.

As I see the lassies tottering around in the Central I wish, for a second, that I was just another weekend warrior, working all week and spending my wages on a Friday and Saturday, high heels and the dancin’ then hame with a hangover. But I always wanted to be different, not like everyone I went to school with who kept to their ain,3 who saw that Glasgow as a dangerous place full of other folk who had made it out of parochial living alive. I longed for the bustle of a cosmopolitan city, like New York or London. Glasgow, where you weren’t seen as posh because your grannie didn’t let you out to go up the park drinking and smoking, would do.

I decide on a whim to go to the pub because the train will be another 40 minutes and it’s too cold to sit on the hard metal seats. It’s the pub in the central, you’ll know it because I think it’s the only one.4 ‘That’s Entertainment’ by the Jam comes on and I remember it’s referenced in the book The Melancholia of Class by Cynthia Cruz. She describes Paul Weller as an archetypal working-class subject, talking about how his performances and lyrics forced a society who would rather workingclass lives remained undetected to confront them in visceral detail. I remember when I was wee I went to the pub that was above what is now Marksies and Boots the Chemist in Central Station. Me and dad had some lunch, or maybe it was me and mum. I used to come into town on the school holidays with my mum and go to her work along the Broomielaw, a few minutes’ walk west along Argyle Street. I’d wander round the office and my pockets would be filled with ten-pound notes and fivers from various folk. Then we’d go with her two work colleagues to a pub called the Montrose, where I’d always get Chilli Con Carne.

It’s all wasteland there now, the Monty long demolished.

I don’t usually go into pubs alone, still paranoid from all those years ago underage drinking in town. I always worry I will get ID’d. But there’s no bouncers here, so I get my gin and tonic and I’m looking for a seat, all confident. It’s nice to be among other folk just waiting; solitary drinkers, groups of loddies. Glaswegian voices bounce around through the music and I think about how I don’t often hear my own voice reflected back to me in daily life. Meanwhile I hear Weller:

feeding ducks in the park and wishing you were far away

At the bar a man says he could go a large sausage supper. A few days earlier I have to explain the concept of a notion, as in I’ve got a real notion for a fish supper to a friend who looks at me with confusion.5 No one seems to know what I’m talking about anymore. My references and turns of phrase feel like a lost tongue, to be deciphered by historians in a hundred years’ time when this particular branch of Scots language is gone for good.6 I feel increasingly like a stranger in my own existence. The city and its art scene seems mostly devoid of Glaswegians, and working-class folk even more so.

I watch a drip hang off the end of a man’s nose and it’s hard not to wipe it as a reflex. Are there regulars here? I see the barman mouth aye it’s quiet to the drippy nose man and assume there must be. It’s easy to forget people still live in the streets around Central Station, what was once the town of Grahamston. Easy to forget my granda’s years of working on Hope Street and having to collect his colleagues from the pub after they had a few too many on their assigned drink break.

He told me how he used to wait for the early train to come in from London with the papers to be distributed, his first job in the trade as he calls it. He worked as a stereotyper, a job which retired with the introduction of modern technology, as did he. He worked near constant night shifts for 28 years, turning night into day, driving home to Victoria Road on a scooter. Once, he was wearing two budgies in a box around his neck for his children. He was stopped at a set of lights and says a policeman standing on the pavement was eyeing him with suspicion as he waited, tweets emanating from his chest.

His father was the ‘gaffer’ and granda went out to work for the Evening News on the Monday after leaving school on the Friday. He was only It’s just the way it was back then. You followed the family line I suppose, one Govanhill boy to the next, two generations meeting at The Allison Arms every week for a drink, on the same day, in the same seat I can imagine. All this until my great grandad went to Leverndale7 and my dad wanted to be a punk, not a printer, and that was the end of it all.

I was born in the town, so to speak.8 Rottenrow9 Hospital was to the north of the city centre, so named after the rough wood fronted dwellings once located there10 or after a row of shabby cottages infested with rats,11 depending on what you choose to believe. All that remains now is a sculpture of a giant metal safety pin; a monument to the Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital, often referred to as The Rottenrow by locals, and a few walls of the original building’s footprint. A few years back I walked up there with a pal and got my photo taken underneath the entrance archway, arms raised gleefully towards the medieval brickwork. Another link to my past reduced to rubble.

I sometimes imagine my tongue being enlarged and turning to stone in my mouth, concrete pouring into my lungs until I can no longer speak. This gallery opening had offered me some comfort, however, set in a former clay pipe factory. The artworks explored the experiences and expectations of growing up as a young man in the West of Scotland. I don’t imagine most of the people there tonight knew of its former life.

I spend the 12-minute train journey home looking through photos on the internet of the Rottenrow in its heyday, beaming nurses with newborns swaddled and ready for the world. December is a well-known time for old Scottish traditions; pipers play out the old year, a tall, dark and handsome man should appear at your door carrying a lump of coal shortly after midnight to be the first guest after the bells ring at Hogmanay.12 I hadn’t wanted to come out. I was late – in there knitting my mum says. My parents lived in the top floor flat at 22 Clarkston Road at this time and I imagine we might have taken a taxi home from the hospital, but also my parents were pretty skint back then so it’s more likely we would have taken the bus. I should ask my mum about this. She told me that the hormones didn’t kick in right away and when I was handed to her immediately after I was born, she thought:

all that for this?

As I walk down Vicky road (Victoria Road is one of the main arteries into the south side of Glasgow), I see Kebabish; it used to be a shop called Babyland, which sold baby clothes, prams and toys. Dad told me that his first job was taking their shutters down in the morning and putting them back up again in the evening. He got the job through my gran who worked next door at what was the Army and Navy Stores. Locavore, a swish wholefoods shop, used to be the Pandora Pub, and the Transylvania Café was a shoe shop, but Campbell’s hasn’t changed in all the years since dad got his school uniform there. He went to Cuthbertson Primary School and I used to look over on to it from the flat of an old lover on Kingarth Street. Memories of these places move through me like the feeling you get when you shudder inexplicably and it’s said that someone has just walked over your grave.

I pass 388 Victoria Road, my dad’s childhood home. The flat my granda tells me they took my dad home to, with my great aunt holding him up to take a look at it out of the bus window. Granda also tells me how he would clean the windows of the flat, attached by a rope around his waist whilst my gran held on to the other end of the rope inside.

Like this, I exist within two different worlds – the Glasgow of conceptual art, openings, residencies, failed applications, networking, rejections and quaffing free bevy at any opportunity; and the Glasgow of my fiercely working-class Scottish family. I want to inhabit both places simultaneously, but as Cruz discusses in her book, this is not often possible. I have to either abandon my working-class roots and assimilate into the middle-class, or as is usually the case, exist as a working-class person in a middle-class world and be invisible, ignored and used as a trope by middle-class artists looking to further their own careers.

Yer like an old wumman cut down

my grannie used to say. Sometimes she called me ‘grannie much’ too. As in are ye a grannie, much? My mum always says to me that my grannie isn’t dead as long as I’m alive because I love curtain twitching and my nose is always bothering me about what my neighbours are up to.

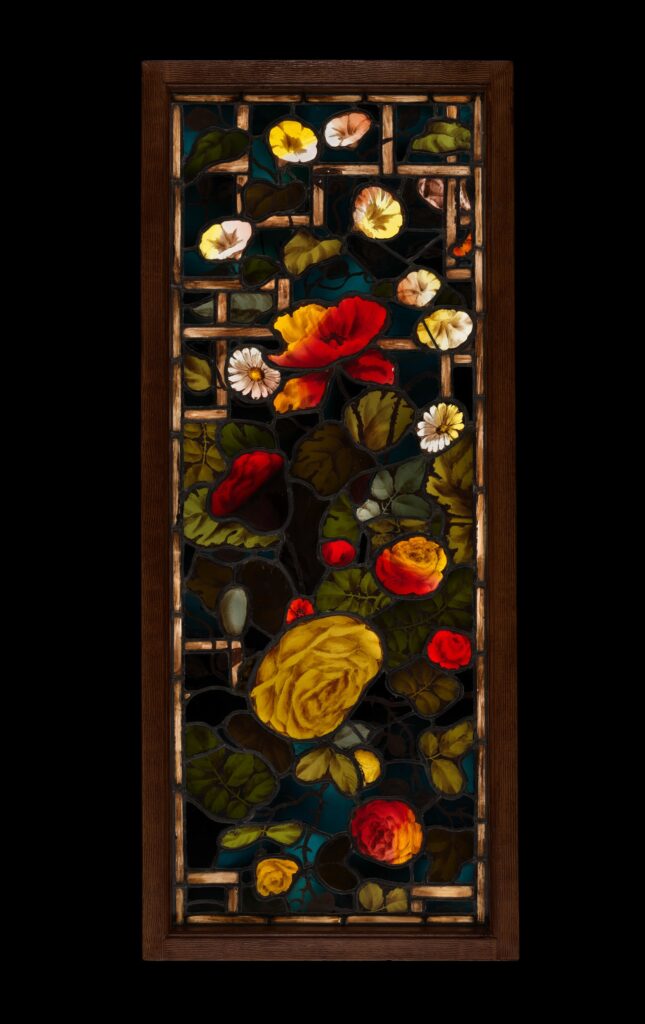

As a wean I was around places steeped in family history as both my parents never moved far from their birthplaces.13 I spent a lot of time in my grannies’ house, surrounded by her collections of plates, thimbles and ornaments. Surrounded also by memories and superstitions: a horseshoe (the right way up of course) at the front door.14 Nickname the ‘housewives’ art gallery’, ornaments and other precious items were revered in the traditional working-class Scots household. These pieces would be kept on shelves or in special display cabinets, elevating massproduced objects to the status of artworks. My grannie’s own range of trinkets instilled an early love of sculptural objects – of the potency and physicality of the stuff of the everyday.

Did your granny not call you fanny as a term of affection? Well, I think it was in affection, maybe I am just a fanny

Wee fanny and big fanny

I alight at Cathcart and walk past the close door of my parents’ first home. When I turn the key to my own flat, I step inside and touch the horseshoe. I move towards the couch and adjust the photo frame on the table which contains an image of my gran in all the messy glory of a Christmas day sometime in the early 2000s. These things remind me of my upbringing, of the working-classes’ long history in the city and the importance of our representation both within the arts and elsewhere. They offer me solace.

- Cowp (plural cowps) – Scots slang for a filthy and disgusting place. ↩︎

- In Scotland pan loaves were traditionally bought by posher folk as opposed to the cheaper, plain loaves bought by poorer folk. ↩︎

- Provincial country meeces, my auntie always used to say meeces as a joke plural for a mouse. ↩︎

- The Beer House, if you’re ever waiting for a train. ↩︎

- A notion is Scots slang for a fancy for something or a craving. ↩︎

- Unless we are also all gone for good. ↩︎

- Leverndale is a mental health facility in Crookston, Glasgow, that opened as an asylum in 1895. ↩︎

- On the 13th of December 1987, at seven minutes past five in the evening. ↩︎

- Scots: Rattonraw. ↩︎

- Rattin. ↩︎

- Raton. ↩︎

- Known as first footing. ↩︎

- Well, mum did live and work in London for a few years, but she stayed in Surbiton and when we went one time, she said she hated how busy central London was. ↩︎

- A horseshoe should always face up the way in an upright ‘U’ shape for good luck. ↩︎