Georgia Horgan

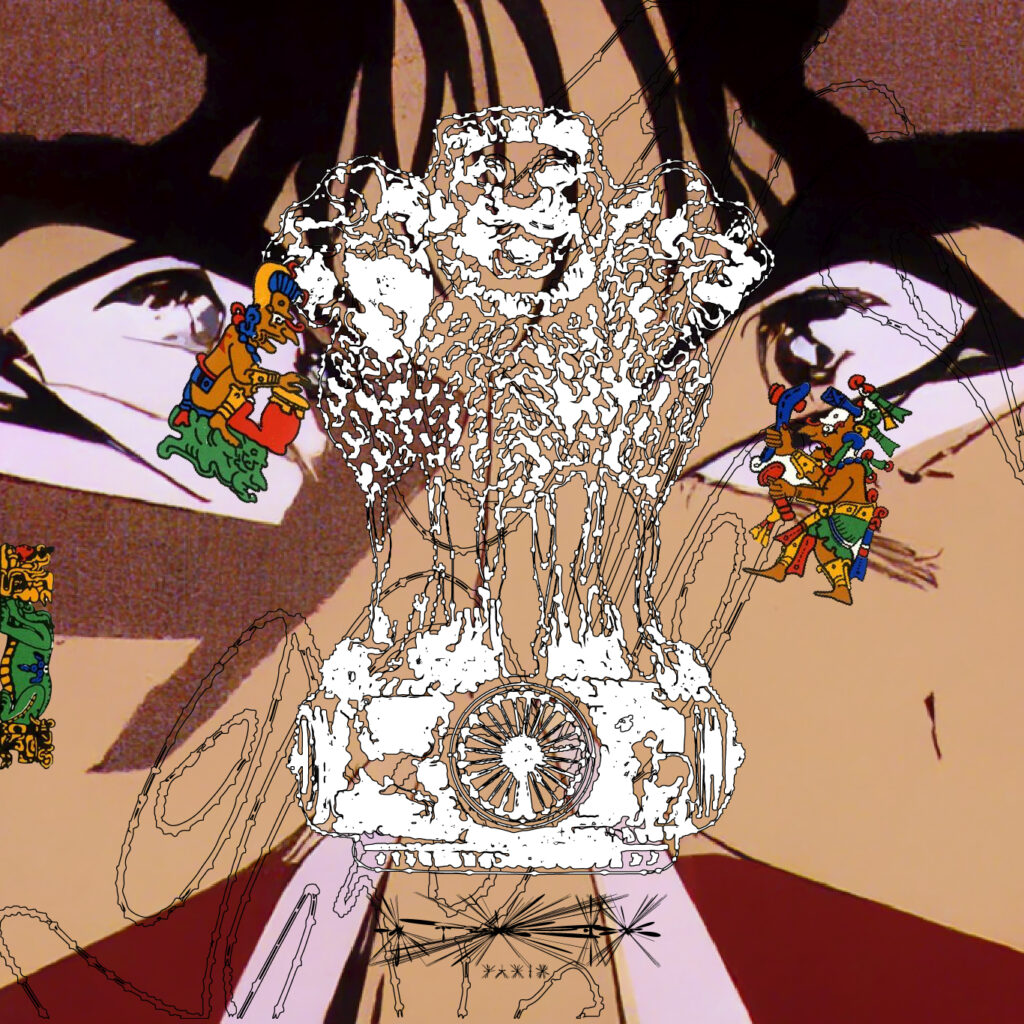

An untitled series of digital drawings by Mexican artist Mauricio Orozco (b.1988, Léon, Guanajuato) depicts Mayan glyphs pasted onto twisted, deconstructed images of characters from Japanese animated sex comedy Golden Boy. The show, which follows the adventures and misdemeanours of horny odd-jobbing student Kintaro Oe, uses his clumsy encounters with various beautiful and powerful women as the premise for the action.

Orozco’s drawings are created through a combination of artificial intelligence and human intervention, producing a masticated pastiche that feels libidinal, digital – almost out of body – yet very much grounded in material culture. His process consists of feeding the female figures from Golden Boy to an algorithm; they’re analysed, reconfigured, chewed up, and spat out. Graphic Mayan glyphs are then collaged onto their ethereal surface by the artist.

This uncomfortable pairing comes from Orozco’s interest in the tension between spiritual and sensual worlds, ruminated on through Eastern and Pre-Hispanic mysticism. In another series of digital drawings, slick, oiled-up hentai1 girls join Mayan deities under the title La rueda filosa que destruye al enemigo (The sharp wheel that destroys the enemy). These works are inspired by, among other things, a 9th century Buddhist text called The Wheel of Sharp Weapons, a poetic discourse on discipline and acquiescence.

Orozco’s interest in these intermediate states – between the sensual and spiritual, the kitsch and philosophical, machine and human, facile humour and ancient wisdom – is tied to his use of Japanese animation, or anime. The erotic dimension of these images, for him, marks a liminal sexual space between childhood and maturity, which concurrently traverses androgyny and a sexed-up binary. Alongside the references to pre-Hispanic cultures, they build a network of familiar symbols to create a bridge between the (assumed to be Mexican) viewer and Orozco’s inner world, in spite of their largely impersonal AI origin.

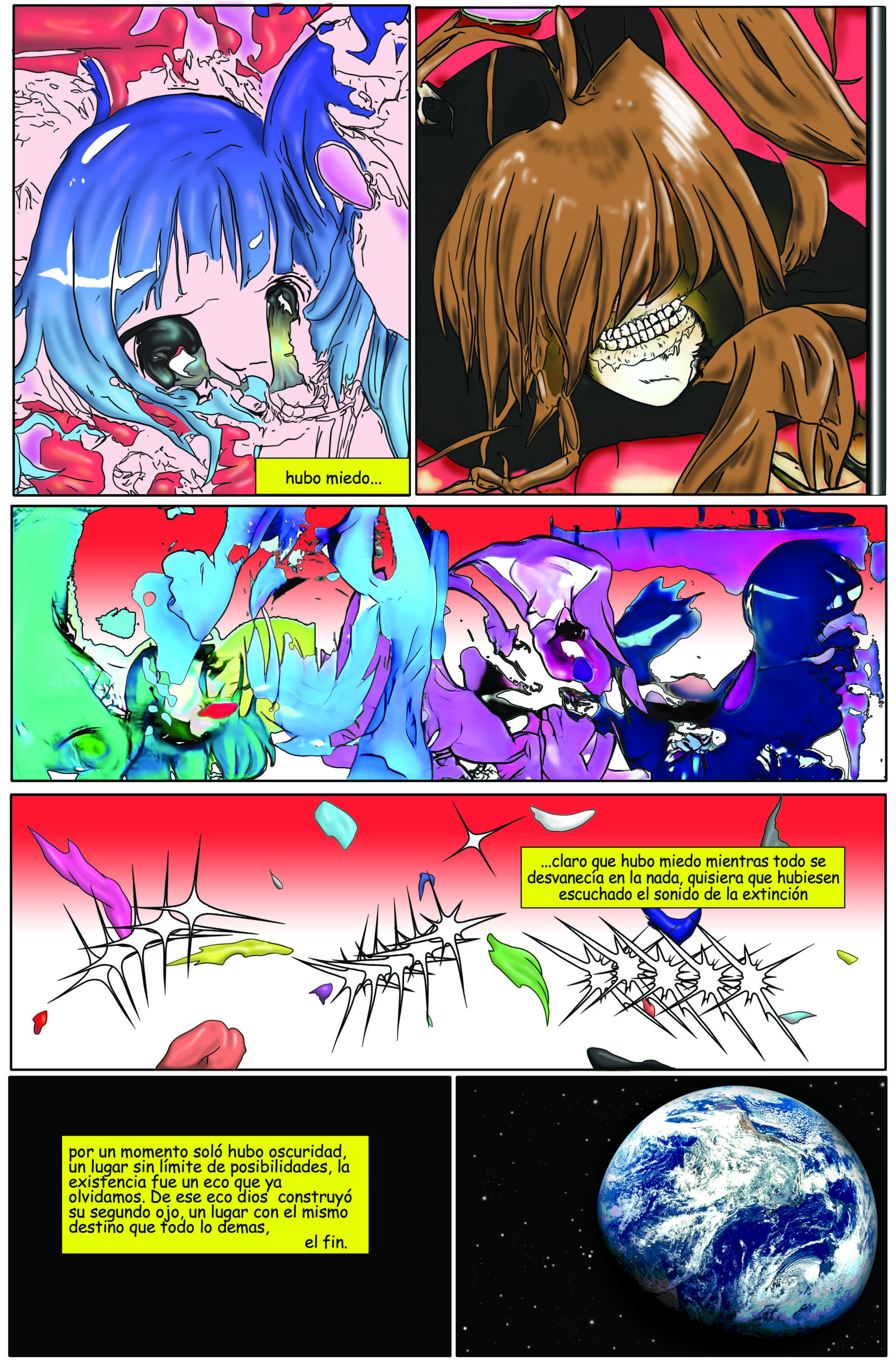

This network of easily recognisable symbols is, by its nature, not idiosyncratic to Orozco’s work. The ubiquity of anime imagery among a generation of Mexican artists is striking, another example being Luis Campos’ (b. 1989, Mexico City). In his drawings and paintings, barbed wire forms, body parts, candy-pop death metal text, floating scalps and cut-up cartoon eyes are spliced together to create a kind of jagged psychedelia. In a cell from the comic O3ZVM II, published by the Oaxacan artist-run Yope Project Space, a skeletal grin with too many teeth emerges from a curtain of rusty red hair.

The source material for these body parts is unmistakable. This hood of red hair once belonged to Asuka Langley Soryu, a character from hit anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion. First aired in Latin America in 1999,2 the show had a remarkable cultural impact across the region. With its stylish combination of apocalyptic futurism and Christian symbolism, the series follows three teenagers who pilot giant humanoid robots to battle mysterious demonic forces known as ‘Angels’ to avert the end of the world.

But it isn’t only Evangelion that appears abstracted in Campos’ drawings. Other cameos include the cut-and-pasted hair of Goku, the protagonistof Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Mars, from the iconic franchise Sailor Moon, who appears clutching her ears and grimacing. Meanwhile, other more ambiguous characters emerge out of a sort of primordial slime, at once pained and ecstatic.

Like Orozco’s girls, most of Campos’ output is computer generated. This is motivated by his interest in the development of visual culture at large, which feeds other references in his work like suits of armour, botanical diagrams, smooth digital gradients, and an overall course tension between representation and abstraction. In an interview, he speculated that AI is the future of image making; soon we will have little involvement in how visual culture is produced.

However, these digital dreams are never neutral. As with any artificial intelligence, it learns from the information provided to it, which in this case, is Campos’ own perception of the visual culture in his immediate surroundings. In this environment anime looms large; in almost every Sunday morning tianguis3 there are stalls pushing otaku4 clothing and paraphernalia. In the historic centre of the capital stands Friki Plaza, a three-storey indoor market dedicated to cosplay, bootleg anime DVDs, statuettes, and other memorabilia.

Once again we’re caught in a liminal space: the area between Campos’ memory and the computer’s desire lines, protracted adolescence and accelerated death drive, all situated somewhere between the future and the past. In the work of Campos and Orozco, and the many others using this imagery – for instance, the recent presentation by Danika Escudero Vanderlinden at art-cum-design showroom Momo Room, or Yope Project Space member Gibran Mendoza – the question of where this infatuation began hangs heavy in the air.

Japanese animation has been broadcast in Mexico since the 1970s. Early animated shows including Kimba: The White Lion, Tetsujin 28-Go and a little later, Astroboy, all became family favourites. It was also during this decade that economic and industrial ties between the two countries were strengthened. After the discovery of new oil fields in Mexico in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis, Japanese industrial interests moved in with greater zeal.

However, it was not until the 1990s that anime truly exploded into the Mexican mainstream. This was, according to scholar Edgar Santiago Peláez Mazariego, due to three main factors: the liberalisation of Mexican television media in preparation for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); the arrival of toy manufacturer Bandai’s LATAM operation; and a global boom in Japanese cultural clout, which created the ideal conditions for a burgeoning fandom in the country.5

Throughout the 1980s, the Mexican economy was transformed, culminating in 1994 with the signing of NAFTA. This process began with the 1983 debt crisis, fuelled by high interest rates, fluctuating oil prices and an economy that (in the International Monetary Fund’s opinion) was too dependent on the state. These conditions caused a run on the peso that led to three-digit inflation. In order to receive international assistance, the United States stipulated that the Partido Revolucionario Institucional or PRI (say pree) follow the IMF’s recommendations and liberalise the Mexican economy.

Between 1982 and 1991, 882 state-owned enterprises were privatised or liquidated; and so the libido of neoliberalism was unleashed. The telecommunications industry wasn’t exempt from the market’s thirst; the president at the time, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, believed Mexican cultural identity was too strong to be overwhelmed by international influences. The networks were liberalised, and having previously held a monopoly over the national broadcasting market, the major public station Televisa had a new competitor, TV Azteca.

Ahead of the opening up of the economy, Japanese toy manufacturer Bandai chose Mexico as its base for a new factory to serve the LATAM region. The emergence of TV Azteca resonated perfectly with their marketing plan: to drive toy sales with broadcast media. Alongside anime studio Toei Animation, they offered TV Azteca discounted rights to the series Saint Seiya: Knights of the Zodiac.

The deal proved to be a huge success for Bandai. The company’s annual invoicing doubled from the previous year, accounting for 80% of the total industry market. In 1996, the partnership attempted to repeat the formula with the airing of Sailor Moon, and as ratings continued to ride high, they made more space in their schedule for Japanese productions. In a bid to compete, Televisa aired Dragon Ball, Dragon Ball Z and Ranma ½, among others, to an equally warm reception.

Anime hype in Mexico reached fever pitch at the end of the 1990s, in line with a global crescendo in the ‘Cool Japan’ phenomenon, as it was later dubbed by journalist Douglas McGray.6 Although the shows began to disappear from public television in the mid-00s – some conservative commentators took issue with some of the more adult themes7 – the demand for anime was well and truly cemented. Fans could continue to access Japanese-made content on cable channels such as Locomotion and Canal 22. Meanwhile, Friki Plaza opened its doors in 2003, brimming with bootlegged and imported goods alike.

This flow of goods was further massaged by the signing of Mexico and Japan’s Economic Association Agreement (Acuerdo de Asociación Económica) in 2005. This brought an even more constant flow of Japanese investment, which was already growing steadily throughout the 90s, thanks to Mexico’s prime position as a source of cheap, youthful labour in the NAFTA economic area. Already raised on a diet of Dragon Ball and Saint Seiya, this labour force, with an average age of 24, was primed for the factory floor.

The intensity with which Japanese visual culture has infiltrated Mexico, from its markets to its contemporary art galleries, is remarkable. It is integrated into the urban landscape so intimately, yet remains so distinctive, so at home in its otherness. Perhaps, as Japanese sociologist Koichi Iwabuchi puts it, ‘cultural otherness sells in the age of globalisation’.8

Between 2003 and 2013 Japanese foreign direct investment flows to Mexico grew at an annual average growth rate of over 20%. Broadcast media and toys actually accounted for a fairly minor portion of this investment; what took the lion’s share was car manufacturing. Over 70% of Japanese investment was concentrated in the automotive industry, for whom Mexico’s strategic position and demographic was particularly attractive.9

The first Japanese automotive manufacturer to invest in operations in Mexico was Nissan, when the firm opened its first plant outside of Japan in Cuernavaca, Morelos, in 1961. The Nissan Tsuru became – and remains – Mexico’s best-selling car and the vehicle of choice for Mexico City’s taxi cab drivers. Nissan’s presence in Mexico crescendoed in 1991, ahead of the signing of NAFTA, with the opening of their A1 Aguascalientes facility. Meanwhile, other brands entered the Mexican market in the wake of the Japanese/Mexican economic accord, including Honda, Mazda, and Toyota, with operations mostly in the Bajío region, Guanajuato, approximately 40km north of Léon.

I work as an English teacher for students at a Japanese sogo shosha10 serving automotive manufacturers in Bajío. English is the language of choice for communication with HQ in Tokyo, as teaching Japanese or Spanish either way is perceived to be too challenging or less useful in regard to broader career development. In one class, a student of mine recounted his experiences working at the newly opened Honda factory in Celaya, Guanajuato, in the 2000s when he too was in his mid-20s. He told me the conditions were awful. Beatings on the production lines, from managers drafted in from Japan, were routine.

This account jarred with the affection with which Japanese culture is generally regarded. Once, a friend showed me a picture of him with a lifesize model of Asuka; he joked that the Japanese-German animated fighter pilot was his girlfriend. Anyway, when I asked him about his love of anime and manga, he said that he suspected the national enthusiasm for the media was about ‘anxiety and agency’. He said unlike American culture (or indeed Spanish, harking back to colonisation), it didn’t feel so compulsory, not so forced down your throat. I wondered if my student would agree.

This ambivalence, or strained romance, is reflected in the work of Orozco and Campos. In the drawings produced by the AI-powered meat grinder is a digital realm where there is a distinct nostalgia for the future, caught somewhere between love and violence, adolescence and cynicism, spiritualism and frivolity. In these twisted animated images there is a desire unfulfilled, yet still pawed at longingly.

Nostalgia for the future feels like a distinctly millennial condition: throughout the 90s and early 00s Mexican television stations beamed humanoid robots, martial arts masters, time-travelling androids and menacing aliens across the nation. Meanwhile, the liberalisation of the economy promised new prosperity, a new era; in the 90s maybe society still believed in the future. And now what?

In the wake of NAFTA, now re-hashed as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), inflation in Mexico continues to rise. The currency is more or less stable, but at $20 MXN to the dollar, it’s nothing compared to the $3 MXN to the dollar enjoyed by Boomers and Gen X at the signing of the NAFTA treaty. What happened to the future? The promise of prosperity?

This condition reminded me of ‘NAFTAlgia’, a term coined by Arte y Trabajo BWEPS, a research group organised by artist-run space Biquini Wax EPS. In their essay of that title, published ahead of the ratification of USMCA in 2017, they reflect on the NAFTA years through a ‘magical realist collective autobiography’. Constructed around a failed relationship with an insensitive gringo boyfriend, the essay describes the intimate experience of this vast macroeconomic exercise.

In their account, the 1994 trilateral agreement with the United States and Canada would not be ‘a vulgar colonial plunder… but a sweet, lubricated honeymoon’. It ultimately ends in a string of broken promises, unfulfilled expectations, and hard fucking work. One of the collective recounts their mother’s attitude to their artistic labour in the NAFTA landscape:

Bourdieu did not reach deep Mexico. Only Honda, Mazda, Nissan and Volkswagen reach into the country’s lawless subsoil, sucking a shitload of water free of charge. For my mother, the work had to be direct, from the body.

I can’t help but notice the honourable mentions for three Japanese manufacturers (and one German, just like Asuka).

Not a month ahead of the beginning of renegotiation, the Office of the US Trade Representative hurriedly published its objectives. A Bloomberg analyst called it, ‘a unilateral announcement after a unilateral list of demands.’11 A key demand was that 40% or more of auto parts are required to be manufactured by workers who are paid at least $16 USD per hour to avoid tariffs.12 This was intended to attract automotive manufacturing back to the United States.

So much for said lubricated honeymoon, it seems. But the Japanese brands aren’t going anywhere, and good thing too, if the gospel of trickle down economics is to be believed. According to reports from an industry newsletter, the cost of moving the plants is just too much. They’d rather pay the duties or just raise workers’ wages. Besides, they’re exploring automating much of the factory floor to mitigate rising labour costs.13

Unlike the States, Mexico and Japan’s honeymoon will be syrupy sweet and glide in nicely. The labour force will be fully automated with metallic roots stretching deep into Guanajuato’s scorched soil. In line with Campos’ vision of the future of image production, this factory floor will do away with the human hand and accept the android’s cold embrace, like Orozco’s tantric surrender. It will feel like the future, have all its trappings, although perhaps not as we had hoped. Love hurts, it seems, these artists’ wet digital visions.

Reflecting once again on the AI-raptured, nostalgic-but-bleak futurity of these works, I’m reminded of the questions that introduce Arte y Trabajo’s state of NAFTAlgia:

Can the millennial lumpen speak?

Do black sheep dream of cholo androids?14

Thanks to the artists, Cheryl Santos and Frankie Ventura for sharing their thoughts and experiences. Special thanks to Lisander Martínez, Professor at the Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan, for her insight and guidance.

- Hentai is Japanese animated pornography. ↩︎

- View the 1999 trailer for Neon Genesis Evangelion broadcast on cable channel Locomotion: https://youtu.be/bBHZ_fN3ljo. ↩︎

- An outdoor market, usually shaded from the sun with tarpaulins. ↩︎

- Otaku is a Japanese word that describes people with consuming interests, particularly in comics, video games, or computers. In Mexico, it’s applied specifically to anime and manga fans. ↩︎

- What follows here is an abridged explanation of Edgar’s analysis of how anime took hold in the Mexican market. His 2019 paper ‘The Global “Craze” for Japanese Pop Culture during the 1980s and 1990s: The Influence of Anime and Manga in Mexico’, is published by Iberoamericana and freely available online: https://waseda.academia.edu/EdgarSantiagoPeláezMazariegos. ↩︎

- Douglas McGray’s article ‘Japan’s Gross National Cool’ was published in Foreign Policy magazine in 2009: https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/11/11/japans-gross-national-cool/. ↩︎

- One particularly vocal critic was Lolita de la Vega, who according to Richard Villegas in his article ‘The Influence of Anime on the Mexican Underground,’ described anime as ‘satanic’: https://daily.bandcamp.com/scene-report/anime-and-japanese-culture-list. ↩︎

- Read the full discussion in his essay, ‘Complicit Exoticism: Japan and its other’: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10304319409365669 ↩︎

- María Guadalupe Lugo Sánchez’s 2021 paper ‘Spatial Clustering of Foreign Direct Investment: The Case of Japanese Automotive Suppliers in Mexico’ outlines this tendency in detail: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S200753082021000200115&script=sci_arttext_plus&tlng=en. ↩︎

- Sogo shosha are Japanese corporations that engage in logistics, plant development and international resource exploration. ↩︎

- Get the full article, from 2017, here: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-19/date-for-nafta-talks-is-said-to-be-released-as-soonas-wednesday. ↩︎

- ‘United States–Mexico–Canada Trade Fact Sheet Rebalancing Trade to Support Manufacturing’ published by the United States Trade Representative: https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/fact-sheets/rebalancing. ↩︎

- ‘Japanese automakers prefer staying in Mexico’, an article published by investment advocacy groups Mexico Now. Other affiliated organisations include Border Now and HorsePower: https://mexico-now.com/japaneseautomakers-prefer-to-stay-in-mexico-than-move-to-the-united-states/. ↩︎

- ‘NAFTAlgia’ is available is available in Spanish via the online magazine Campo de Relampagos: http://campoderelampagos.org/critica-yreviews/20/7/2017. ↩︎