Michelle Williams Gamaker is a moving image artist and lecturer based in London. Her films trouble the colonial, imperialist narratives of 20th Century British and Hollywood cinema, recasting marginalised characters as central figures – ‘fictional activists’ who both vocalise the injustices they have experienced and act out new alternatives. Across her practice, Williams Gamaker confronts and disturbs the sedimented institutional languages that fail to account for the ways that race, class, gender and queerness variously shape experience. In this interview, we talk to Williams Gamaker about the joys of escapism and interrogation, fictions that bleed into reality, and the languages that permeate her practice, the words that return.

KIAH ENDELMAN MUSIC: I recently watched the 2020 a-n Artists Council ‘Artists Make Change’ conversation between you and Jade Montserrat, where you talk through your friendship and collaboration, and the shared impulses that guide your work and working relationships. I was struck by the way you spoke about language, the idea that it has a ‘lived emotional resonance’ built on the ‘pain… and longing… and… speculation’ carried with it through its histories, across its lives. You also spoke about the freeing effect a lack of formal training has had upon your work with language as an artist, and I wondered about this tension between language as material and experience. I thought this could be a jumping off point, to ask you to speak through your relationship to language and about its role in your work?

MICHELLE WILLIAMS GAMAKER: Working with language as a material is something that I have grown into. I should note that if I speak or write with confidence now, it wasn’t always this way. Utilising the materiality of language counters the passivity that can occur when words are used without thought. An example comes from teaching, where words and their application are essential to understand and support the progress of students’ work. The language of one student (their specific vocabulary) inevitably differs greatly from other students – and I try to meet each individual halfway, to share in their linguistic register. This is, of course, totally subjective, but in this way, I think I have been accumulating language and the way people speak actively since I started to teach in 2006. During a tutorial, there is space to play with language, to find modes of expression that build trust and allow for feelings to be shared. I often find something unexpected emerges in the construction of a sentence, and in moments like these I ask my students to hold onto what they have just said – because it is often very revealing about what they need the work to become and what drives them to make it.

The conversation with Jade is also an example of a shared language that we explore, built on the trust within our friendship. The pain, longing and speculation that I intimated sits within language is something I think we both explore in our practices, for Jade through drawing and spoken word and for me through scriptwriting. I think once we acknowledge that language is a repository of experiences, it cannot be separated from one’s own history and a wider cultural inheritance that ultimately impacts how we think. I know that I speak in a ‘coloniser’s tongue’ and it sits uncomfortably in my mouth. I try to not wield words as a weapon, but to understand the scope of their violent power – this sometimes involves writing from the imagined position of those who have and wield power. I find the language I speak to be a soup of what was taught, what had to be rejected because in effect it was rote learning, and what was imbibed from others (especially an affinity with the world of fiction and its characters). This constant play with the words I speak creates a space to subvert and explore the ‘lived emotional resonance’ of language. Acknowledging this has helped me to relax when I use words as I feel they more and more reflect my desire to speak and be heard.

KEM: I wanted to ask about the role of scriptwriting in your work as an approach to both language and the visual. Perhaps there are two queries here: firstly, how do you start? Does image or text come first? And, secondly, how does the script act as both a formal structure and critical tool?

MWG: Images often come first. Usually a trapped image from the past, for example a film still or a scene that haunts me. I often fixate over the problems of an image and usually the only way to dislodge it is to revisit it and reimagine it through filmmaking. As a student, Chris Marker’s 1962 film La Jetée left a strong impression on me. The premise is that a time traveller is sent back to the past because of his capacity to remember an image from his childhood – I loved the possibility that an image from the past could find a solution for the present. A lot of my films reimagine scenarios proposing alternative conditions for characters.

The script is a tried and trusted tool to indicate dialogue and action, and I really enjoy the formal qualities of how a script can share visual motifs and concepts with such economy and beauty. I am indebted to my partner Elan, who is a screenwriter, and who gave me the basics of scriptwriting, but I have always been a reader of screenplays for their accessibility. I tend to follow my scripts quite closely when I work on set. It’s important that my actors don’t detour greatly from the text and my role is to try to transform the words I have written into the specific image I have in mind. In this way, the script is a formal blueprint for the crew, but as a document, it has a critical function, because I often write from a space engaged in the politics of the source material the images derive from. I have started to think that the script has become the only way I start to make – which long term might feel limiting or possibly too controlling – but at present it feels expansive. It allows me to set out my vision for the work I want to make and enables precision in the form. I have to carefully work out how to bring the politics to the fore without being too didactic. A script that has been laboured over through several drafts and read by my collaborators is something that I ultimately want to share through the final film and the text, where all my intentions are laid bare. They will always differ, but I love how the script marks this journey.

KEM: A project I wanted to ask about was the June 2020 statement you wrote together with Jade Montserrat and Cecelia Wee, ‘We need collectivity against structural and institutional racism in the cultural sector’. Not a script, but certainly another kind of directive writing, the clear language and content of this statement felt so crucial in face of the stream of public declarations of anti-racism and ‘statements of commitment’ that were typically left at that – as statements, unenacted. How does this piece feel two years on?

MWG: This text felt so urgent at the time, as I recall we had just witnessed the distressing and needless death of George Floyd, which resulted in a resurgence in Black Lives Matter activism (or rather a resurgence in press attention for BLM, as the activism never went away). We felt compelled to write the text because of the evident institutional performativity within the cultural sector that, as you mentioned, appeared to stop short of action. Our statement enabled us to vent using a precise knowledge of our combined lived experience within the arts and academia. I remember that we returned to the text over and over again, and there were many allies (including Tae Ateh) who read the text and questioned our words. What resulted felt like a rigorous spewing of bile and toxins after working under untenable conditions. It felt long overdue.

After publication, Cecilia, Jade and I were inundated with emails by wellmeaning organisations and individuals asking if they could help or if they could host our work. Ultimately, we just didn’t have the capacity to respond to it all, nor did we feel the institutions that reached out to us knew what they wanted of us. When we wrote the text, we were not proposing to find a solution or solutions to the problem, and I think what Cecilia raised in the Harsh Light talk was that we are time and again asked to ‘fix’ things that the institution is lacking – either within their programming or to temporarily improve the optics of their staffing team. Two years on, I think there have been significant improvements across institutions. I can only speak for myself, but I am beginning to slowly shrug off the gnawing feeling of tokenism that followed most invitations. I can’t say if this says something about where I am in my career, or that things have genuinely changed, but I would like to hope it’s the latter.

KEM: You have described the focus of your work as Fictional Activism, an approach to art and filmmaking that performs ‘potent acts of fictional treachery’. This construction reminded me of a conversation between Saidiya Hartman and Arthur Jafa, where Jafa suggests – or provocates – that ‘nonfiction needs fiction, but fiction doesn’t need non-fiction.’ Hartman responds: ‘the difference between fiction and non-fiction has everything to do with…who has the power and authority to advance truth claims.’ This careful negotiation of the terms by which we define experience felt significant to your work. I wanted to ask – what counts, for you, as fictional and what as ‘real’ activism?

MWG: Firstly, thank you for sharing this negotiation by Hartman and Jafa – I love what they bring to light here – the space of fact and fiction is a very slippery terrain. I do agree with Hartman that power and authority play a key part in storytelling, be it a perceived ‘fiction’ or presented as ‘truth’. I suppose the ‘fictional’ and the ‘activism’ that I speak of is being applied with a specific lens in mind: Western cinema’s Hollywood and British Studio films adopted a very powerful hold over global audiences in the 20th century, and to a certain extent their ideological distribution of images still dominates popular culture, despite other cinemas and voices having more accessible platforms to share their work.

Fiction is almost impossible to separate from ‘truth’ and I try to incorporate the docufictional into my writing – so that something I know, or the experiences of the performers I work with can sit inside the fiction. When I apply the word ‘activism’ I am aware that my engagement with the term is conceptual. I do not wish to belittle the essential work of activists who engage in supporting others where it quite literally could mean the difference between life and death.

However, the theoretical application of activism I am working with seeks a narrative reparation for former fictional injustices, which supported a legacy of misrepresentation that I feel impacted many people’s self-worth, either in not being able to find decent screen representations of themselves in their formative years, or in the participation in the racist legacies of cinema, which contributed harmful stereotypes over more truthful representations of individuals or communities.

KEM: Perhaps this is a related, if slightly tangential, question. You’ve spoken about your first, childhood experiences of cinema, watching films at home on your TV, as a kind of escapism. How do escapism and engagement, the joys of both falling into and interrogating something, play out in your practice?

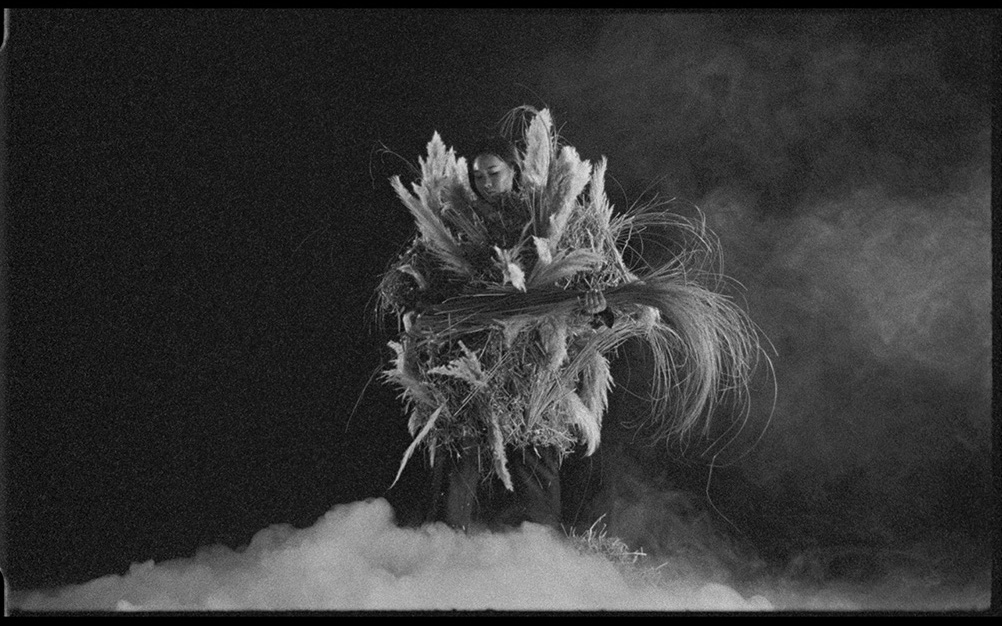

MWG: Well, I think I have a natural predilection to escapism – partly because I love to daydream and find it a useful tool for thinking about the work I want to make. I absolutely needed films as a child and teenager; to escape into their lavish and epic worlds. And I found deep comfort in televised cinema; its featurelength duration, its folly, its drama and artistry as a means to temporarily shake off more routine or banal parts of my life. Today, I want to share this escapist dimension with others. For example in my film The Bang Straws (2021) I genuinely wanted to recreate a scene in which Austrian-German-American actress Luise Rainer is covered head to toe in straw during a storm sequence in Sidney Franklin’s 1937 film The Good Earth. The recreation of this sequence for me was about questioning who gets to perform in films (an ongoing concern in my work) and subsequently who gets to make films? It is more than likely that Rainer’s body was swapped out for a stuntman, bringing the question of gender to the fore too.

I love how you have phrased this question, because there is something joyful about immersing yourself in something, but that moment of revisiting can’t simply be about repeating. I think a great deal of historical films failed to interrogate what they were representing and as a result are structurally lazy. By interrogating the thing you love, there is the possibility of critical affection that enables me to deconstruct and scrutinise something in multiple ways. This has been the case with my ongoing fascination with British directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. This began with their 1947 film Black Narcissus, which is the source film of my Dissolution trilogy (2017-19) and continues with my latest production Thieves, which revisits two films from 1924 and 1940 of the same name: The Thief of Bagdad. This will be my first film in Fictional Revenge, and here I will seek a fictional bloodletting for the racist practice of so-called brown/black face, which meant many actors of colour were denied roles in favour of white actors’ poor substitute characterisations of indigenous communities. The script also broadly confronts labour rights for workers and considers the historic (possibly present-day) class structures of film sets. One example utilises the Indian protest model of the gherao, which I learnt about from interviewing Dr Adrishya Kumar in Kolkata, whereby my actors will confront the director Michael Powell and screenwriter Lotta Woods by encircling them until their demands for screen justice are met.

KEM: Your recent work with UAL for the Decolonising Archives project, ‘“Knees and Breasts are Mountains”; the art school reimagined’, speaks to this negotiation between the real and the fictional, the institutionally scripted and the creatively produced, the imagined otherwise. Could you speak about what it was like to work with Chelsea College of Arts and the Henry Moore Archive? I was particularly interested, when reading your script, in your decision to assume the role of ‘External Examiner’ – how did the relationship between the supposed ‘objectivity’ required of this position and the steeply subjective space of the archive play out?

MWG: I applied for the Decolonising Archives project because I saw an opportunity to bring the script into the space of the art school. This is something I had tested in a script called Parting Gestures, a loose play proposing a conversation between me and the graduating students of the 2017, which appeared in the Goldsmiths degree show catalogue. I had also in 2018 turned a co-curated exhibition with Nick Norton and Catriona McCara into a script for a programme titled Library Interventions: Moving Knowledge at Leeds Arts University, so there was a precedent for wanting to construct a scenario within an institutional context. I wondered if an archive, often understood as a static repository of factual content, could have some subjective interventions around it, without skimping on criticality.

Through my work with Women of Colour Index (WOCI) Reading Group between 2016-2019, together with co-founders Samia Malik and Rehana Zaman, we worked with WOCI’s collection of slides and exhibition ephemera collated by artist Rita Keegan, who indexed Women of Colour artists working in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s. This invaluable archive evidences the precarious nature of practice for marginalised identities and the hardwon position of these individuals who fought for their work to be exhibited and received with parity in an evidently more racist and resistant landscape for artists of colour within the arts. So while I don’t take archiving lightly, I wanted to write myself into one that had little or no trace of artists like myself with diasporic, migrant histories.

I chose to work with two archives from Chelsea College of Arts, as it was the one part of UAL that I had the least connection with. With this in mind, I developed the role of a self-appointed time travelling External Examiner, partly as a tongue-in-cheek response to my marginality within institutions, first as a student, and then as a Senior Lecturer, but also, because of that marginality, as a way to justify my reinstated presence in Chelsea School of Art’s (as it was then called) ostensibly white teaching and student body.

In the Henry Moore Archive, there was a fascinating picture of the artist as his sculpture, Two Piece Reclining Nude, was installed in 1964 outside the art school’s Manressa Road campus. I wanted to use the holes, commonly found in Moore’s work, as a device to look through and beyond to the histories of overlooked artists of colour within art schools. I had some fun photoshopping an image of myself, posing with a clipboard in hand as the External Examiner.

The relationship between the supposed ‘objectivity’ required of this position and the steeply subjective space of the archive played out through a series of conversations, firstly with artist Keith Piper, who was part of the first Black artists only show, The Devils Feast, in 1987. I also corresponded with Gavin Jaantje’s Chelsea’s first Black Senior Lecturer, and Chila Kumari Burman, who also appeared in The Devils Feast. In the last instalment of the script, I travel to 2020, to speak with Sarah David, Maryam Hina Hasnain, Nisa Khan, Zichen Wang and Chuni Wu, all graduating Fine Art MA students whose studies were deeply affected by the impact of the pandemic. It felt important to mark the art school in the 60s, see the political landscape shift in the critical decade through the work of the Black Arts Movement and to return to be in dialogue with recent graduates about how they experience the college today.

KEM: I also wanted to ask about your experience with A Particular Reality. What has it been like to work within this collective? To develop an alternate arts education that formal institutions have continually failed to provide, for both you and for your students?

MWG: The ever evolving inter-institutional collective A Particular Reality (APR) is moving at such a pace that we have had to use some of our time this year to map what we have achieved and also to work on funding to deliver a sustainable programme for the coming academic year. What began as a collaboration between Kingston School of Art and Goldsmiths in 2018, has grown to include Manchester Metropolitan and Middlesex Universities. To give a brief overview, APR is open to all students, but our focus is centred on supporting BIPOC students to express their creativity and to explore their cultural identity through their work, if this feels relevant. We are developing a responsive extracurriculum that feels self-generating and is reaping positive learning experiences for our participants. We are working with students to improve their experience of art school, with anti-racist teaching practice as part of this endeavour. We also hope that APR enables more connections for students from intersectional backgrounds, who commonly share their experiences of disconnection and isolation on their fine art course. We are driven by the need to co-investigate and collaborate with our students, and where possible invite them to lead in the delivery of events. This was the case with our focus on artist filmmaker Sutapa Biswas this year, where we took students to see her retrospective at Kettle’s Yard and then later in the year our students prepared questions alongside Abhaya Rajani for an intimate roundtable session with Sutapa at Autograph ABP to discuss her latest film, Lumen (2021).

The cross-pollination of staff and students across Goldsmiths, Kingston, Manchester Metropolitan and Middlesex is so galvanising because we are sharing resources and skills and somehow bypassing the restrictions of each institution. I love this under the radar, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney ‘Fugitive’ approach, as the entity of APR is polymorphous as a strategy of resistance from the current model of Higher Education that we are working within.

KEM: To end, I thought we could return to the start, to the conversation between you and Jade. Together, you spoke of the movement of language, of the harm it can cause but also of how, as you say of Jade’s words, another’s language can act as a kind of balm. I wondered if you could talk a little more about the intimacy and weight of another’s words shaping your own, shifting your experience?

MWG: Thank you for bringing me back to this interview – I do need to watch it again, because it was one of those many Zoom conversations in a difficult year, but it felt warm and familial to be talking with Jade. Wren, my youngest was very small at the time, so this was a blurry moment of survival within the pandemic and as a parent of a young baby! The possibility of another’s words shaping my experience, is something that I feel makes one think about empathy and reciprocity. If I read Jade’s words, or look at them on my wall at home, I cannot fully know the nuanced detail of her experience, but I can feel an echo of it, its sting or softness, depending on the tone. I have been working with my performers to incorporate their experiences into my scripts, and this docufictional aspect is very important to me as I want those who perform in my work to be more than vessels for content I want to share. I love the possibility that their history, the ‘intimacy and weight’ as you describe it, mingles with the work and something new with a pulse results in the exchange. I think with Jade’s words, I was referring to her commision for the London Underground. I carried her text ‘Dear Friend, I know that you and you alone possess peace’ and I have often been moved by Jade’s capacity to write a sentence or stanza that holds simultaneous doses of love and rage.