In our interview for this issue, Momus editor Sky Goodden begins a discussion on the idea of ‘crisis’ with a quote from Toni Morrison: ‘I insist on being shocked. I am never going to become immune. I think that’s a kind of failure to see so much of it that you die inside. I want to be surprised and shocked every time.’ Similar sentiments appear to thread their way through this issue. In many of the pieces there is a sense of working against inertia, against prevailing attitudes and their hardening in moments of crisis. Often, that effort produces a certain unease, which manifests in unsteady movement – the writing cuts, splices, pivots, shifts tense. The images chosen to accompany the writing reflect this, seeming to turn in on themselves, with scenes and objects that feel difficult to pin down. Together, they register a need to return again and again to the task of marking extremity in the everyday.

For many of the contributors, time is of particular concern. In Tillie Olsen and Time’s Coal: Some Verses on the Limits of Practice and Discipline, Laura Haynes navigates the constraints of late capitalist time on the woman writer. Questioning a societal demand for the day’s optimisation, Haynes asks instead, where is the good-enough setting? In our Hybrid column, Jessica Higgins’ Now, for the doubters and the sceptics moves through the syncopated rhythms of office hours, clock-time and domestic boredom, cutting between Jane Arden’s film Anti-Clock and Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star. In Do You Ever Remember Books You Haven’t Read, Brent Garbowski recounts a trip across Pennsylvania, tasked to pick up thousands of books for a Jim Lambie show in noughties New York. For our Writing Through column Rebecca O’Dwyer considers Rosemarie Trockel’s Manu’s Spleen 1, reflecting on its graveyard scene from the perspective of post-lockdown Hamburg, noting a world picking up where it left off. Aïcha Mehrez’s essay Ethically Surfacing Museum Connections with Empire and Slavery addresses the ongoing harm caused by Tate’s decision to frame its colonial history in neutral terms, and its refusal to acknowledge the institution’s power to shape national narratives.

Similar themes are outlined in exhibition reviews by Natasha Ruwona and Maria Howard. Ruwona looks at how Drink in the Beauty at GoMA falls short of its aims to address ‘current debates on climate justice and legacies of the British Empire’. At Tramway, Howard reflects on Amartey Golding’s Bring Me to Heal, its meditation on the generational trauma of colonialism and the iterative rituals that become a form of processing and resistance. Elsewhere, Ruth Gilbert reviews Life Support: Forms of Care in Art and Activism, last year’s major show at Glasgow Women’s Library. She looks at the ways care has been taken up by various women artists not only as a necessary tool for survival, but an ‘articulation of hope’. In a review of Thriving in Disturbed Ground at 16 Nicholson Street, Gwen Dupré questions the curatorial assertion that female empowerment can be achieved through reclamations of vulnerability and spirituality. Calum Sutherland writes on the assimilation of artisan materials into tasteful contemporary art via Tonico Lemos Auad’s Unknown to the world. In light of their shared experience of growing up in Belfast, Neil Clements considers Cathy Wilkes’ installation at The Modern Institute. Paul Barndt’s book review takes us through David Hoon Kim’s Paris Is a Party, Paris Is a Ghost, touching on language and translation, love and wasted time.

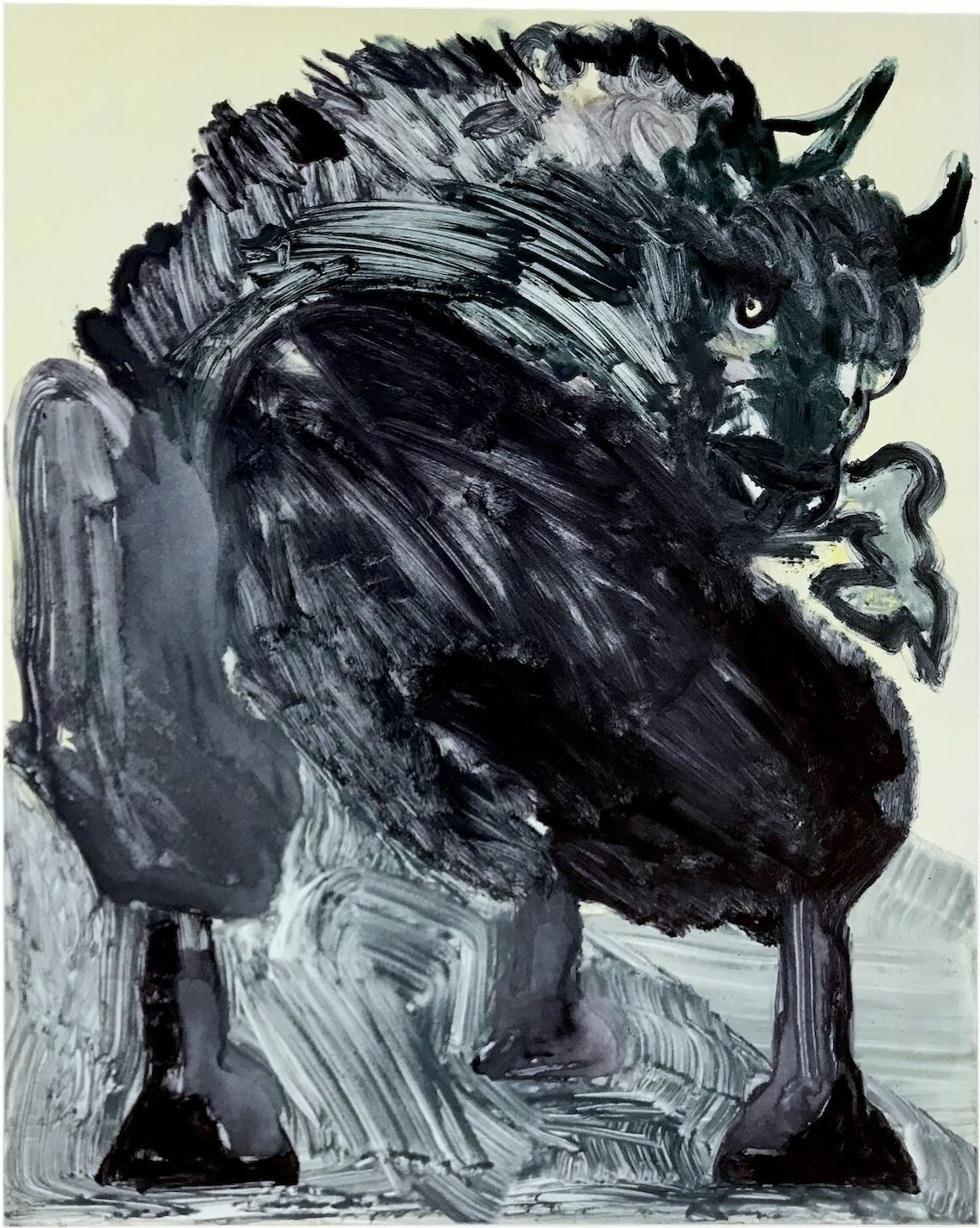

Frances Stanfield, Yellow Bull, 2020, monotype on Somerset Paper, 70 x 50 cm.

Our cover image, Poppy Jones’ Soul & Body (2021) depicts a tan jacket with one button fastened and one undone. Painted on suede, the work repeats itself, the art object and its subject indistinguishable. Cropped sharply and framed in aluminium, it focuses all attention on its detail, avoiding any definitive narrative suggestion. Jones builds the image through lithographic printing and washes of oil and watercolour in what becomes a palimpsest of process and routine. The nap of the suede bears traces of a hand passing, evoking both the immediacy of painterly gesture and the intimacy of dressing.

After a glimpse of how things could be done differently, it is frustrating to witness a return to normal. Towards the end of the interview with Goodden, a question arises of what to do with the unease of this moment. She suggests the tension, if not defined in terms of crisis, can be generative, a well of energy for new conversations and practices. In Soul & Body, as with the rest of this issue, something hopeful emerges from the refusal to stop looking, despite the pressures of time and exhaustion. The past is unsettled in service of the present, and inertia is held at bay.